Our character is basically a composite of our habits. Because they are consistent, often unconscious patterns, they constantly, daily, express our character.Stephen Covey

Check Out These Highlights:

Do you have any bad habits? Come on, you know what I am talking about! If we know what is considered a good versus a bad habit, why do we have so many darn bad habits? Most of us have tried to lose weight, get in better shape by going to the gym every day, eat healthier, stop smoking, and the list goes on and on. So if we know what makes a habit good or bad, why do we still have so many that often seem to be out of control? What if I told you there is an almost foolproof way to really change up your behavior patterns – Do I have your attention?? Is this even possible?

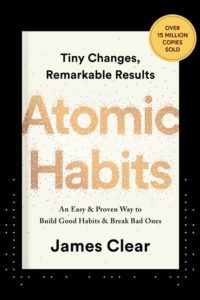

Today, your host Connie Whitman speaks with James Clear. James and I are going to discuss his new book, Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. We are going to break down how to actually change or form a habit that will stick.

Atomic Habits With James Clear (EP. 108)

As always, I’m happy you’re here. As we go down this journey together of changing the sales game, I hope that you feel my passion and that I’m creating a movement. We’re going to shift the word sales so that icky, sleazy, and manipulation don’t even come into our brains. When we hear the word sales, we know it’s about service, love, caring, and the respectful exchange with whatever it is that you’re selling or whatever your business is that you’re offering. Join me on that mission and we can make that change together.

The motivational quote I wanted to start with is by one of my favorite leadership experts ever. It’s by Stephen Covey. He says, “Our character is a composite of our habits because they are consistent and often unconscious patterns. They consistently daily express our character.” Do you have bad habits? Come on. You know what I’m talking about. We all have them. If we know what’s considered a good versus a bad habit, then why do we have so many bad habits that we use every day?

Most of us have tried to lose weight, get in better shape by going to the gym every day, eat healthier, stop smoking, and the list goes on and on. If we know we are making those good habits or those choices, why do we still have so many that often seem to be out of control or feel like we don’t have control? What if I told you there is an almost foolproof way to change your behavior patterns? Do I have your attention? Is this even possible? The answer is yes.

In this episode, my guest is James Clear. We’re going to discuss his new book, Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. We’re going to break down how to change or form a habit that you’ll get to stick to. James is a writer and a speaker focused on habits, decision-making, and continuous improvement. You’ll hear his story and understand that. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Entrepreneur, Time, and CBS This Morning. He’s a regular speaker at Fortune 500 companies. His work is used by teams in the NFL, NBA, and MLB. I’m not sure why he is not in the NHL. We’ll talk about that.

Through his online course, The Habits Academy, James has taught more than 10,000 leaders, managers, coaches, and teachers. The Habit Academy is the premier training platform for individuals and organizations that are interested in building better habits in life and work. James, thank you so much for joining me. Your book is revolutionary.

About James Clear:

James Clear is a writer and speaker focused on habits, decision-making, and continuous improvement. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Entrepreneur, Time, and on CBS This Morning. He is a regular speaker at Fortune 500 companies and his work is used by teams in the NFL, NBA, and MLB.

Through his online course, The Habits Academy, James has taught more than 10,000 leaders, managers, coaches, and teachers. The Habits Academy is the premier training platform for individuals and organizations that are interested in building better habits in life and work.

How to Get in Touch With James Clear:

Thank you so much. I appreciate that. I’m very happy to be speaking with you as well.

My first question before we jump into the book is why not the NHL? What’s going on?

I do have a few hockey players who are reading but with the other three sports, I have some of the coaches who are on my newsletter list. I guess I need to throw the NHL on there as well.

Yes, you do. That’s a hockey mom talking to you. Thank you for fielding that one off the cuff. In your book, you described this. How do peer pressure and social norms influence the actual habits that we formulate?

The Four Steps Every Habit Follows

In the book, I break habits into four stages. Social norms heavily influence what I call the second stage. Let me go through the four stages real quick and then I’ll answer the social norms question. Every habit has these four steps that it follows. The first step is what we commonly call a cue, trigger, or prompt. It’s something that gets your attention. You walk into the kitchen and see a plate of cookies. Often the cue is visual, but it doesn’t have to be. In many cases, it is.

The second step is what I call the craving. Essentially your brain makes a prediction. You see something or pick up on a bit of information about something you hear or touch, then your brain predicts what is going to come next. You see the plate of cookies and predict, “This is going to be tasty so I should eat them.” The next stage is the response. You go over and eat the cookie. The final stage is the reward. That’s the benefit that you get from the action. In this case, the cookie tastes good.

You can imagine, however, that your predictions vary depending on the state or the context. If you ate a big dinner in the other room and had a few cookies, then you walk in and see another plate of cookies in the kitchen, you might be like, “I’m stuffed. I don’t want to eat anything.” The difference between the prediction you make and the craving you have depends on your current state.

How Social Norms And Peer Pressure Influence Habits

This is where social norms and peer pressure come into play because in many cases, the habits and behaviors that seem attractive to us are the ones that go with the grain of our culture, norm, or social tribe. Society leans heavily on us all. We have all sorts of habits that we fall into, mostly because they’re like a shared expectation among the groups that we’re in.

If you pull up to a stop sign, pretty much everybody decides to stop there. If you go into an elevator, you turn around and face the front. If you have a job interview, you wear a suit and tie, a dress, or something nice. There’s no reason that you have to do those things. You could wear a bathing suit to a job interview, roll through stop signs, or turn around and face the back of the elevator instead of the front. You don’t have to do that stuff but it would violate society’s expectation or the shared expectation of the group.

That’s true not just on a big level like on the societal level of what it means to be an American, French, or something like that but it’s also true for the smaller groups that we’re part of like being a part of your local CrossFit gym or volunteer organization or being a member of all the neighbors on your street. Every one of those little tribes has a set of shared expectations. Those social norms can either nudge you towards certain habits or prevent you or nudge you away from others.

The key here when it comes to building better habits is to join a group where your desired behavior is the normal behavior. If it’s normal behavior within the group, then you’re going to have a good reason to stick with it. Whereas if it goes against the grain of the group, it’s going to be challenging for you because you’re going to feel like you’re battling the expectations of everybody else.

The key when it comes to building better habits is to join a group where your desired behavior is the normal behavior. Share on XI’ll add a second caveat to that, which I don’t hear people talk about very often but is crucial, which is you want to join a group where your desired behavior is normal behavior and you already have something else in common with them. The only reason you don’t want to violate the norms of any particular group is because you want to be friends with them and belong with them. If you already have something else in common with them, then you have a reason to bond and be friends over that. You can then start to pick up the desired thing that you want to build along the way.

To give you a concrete example, my friend Steve Kamb runs a company called Nerd Fitness. It’s about getting in shape but he writes articles and it’s oriented towards people who identify as nerds, people who love Star Wars, Batman, Spider-Man, the Marvel Universe, Legos, and all those sorts of stuff. You can imagine if you’re trying to get in shape for the first time, that can feel intimidating.

You feel out of place in the gym. You don’t feel like you belong. You’re not sure what to do, but if you can bond with the rest of the group over your mutual love of Star Wars, then you can become friends with them and then you start to pick up the other stuff. It’s like, “They workout all the time too and I’m friends with them so maybe I should do it as well.” Having those connections to build friendships and bonds is a way to turn peer pressure to your advantage and use social norms to make habits more attractive and enticing.

I love that whole concept. Do you find that people will put themselves in positions where it’s comfortable and they can be friends in an unhealthy manner? They then justify like, “I’m overweight but all my friends are overweight too.” Do you see that as well?

Habits Can Work For You Or Against You

It’s something that is true for almost all habits, which is habits can be a double-edged sword. They can either work for you or against you. In the book, I laid out these four steps of behavior. From each step, we have a law. For Q, it’s to make it obvious because you want the cues you’re going to have to be obvious. For the craving, you want it to be attractive so make it attractive as the second law, and then make it easy and satisfying. You can invert each of those four laws to make it easier to break a bad habit because these things can work for you or against you, so make it invisible, unattractive, difficult, and unsatisfying.

The question that you brought up is true. There are research studies that show this on both ends. For example, one study looked at 20,000 people over multiple years. They found that if you have a friend who gains weight, you are 57% more likely to gain weight yourself, even if that friend lives 500 miles away. It’s the same thing on the other end. If you have a spouse who loses weight, 30% of the time, the other partner will lose weight as well. Peer pressure can work for you in both directions. The point here, and this is the central thing that I was getting to anyway, is that we take on the habits, behaviors, expectations, and norms of those people who are around us. We need to think carefully about who those groups are. Sometimes that can work for us and sometimes it can work against us.

Habit Formation

You hear business leaders and thought leaders say all the time, “Look at the five people that are closest to you and that’s why your life is where it is.” Good or bad, you are a measure of who you surround yourself with. It’s the same thing with habits. Well said. James, how long does it take to shift or create a new, hopefully, better habit?

Might be the most common question that I get is, “How long does it take to build a new habit?” People have heard varying answers to this like 21 days or 30 days. There’s one research study that the average is 66 days so a lot of people are throwing that out. It is true on average, that study found that it took about 66 days. As a general rule, that’s a decent way to set your expectations like, “This is going to take a few months. It’s not going to be a quick fix.”

However, even within that study, the range was very wide. If it was a very easy habit like drinking a glass of water at lunch, it only take a few weeks. If it was something more difficult like going for a run after work every day, that would take 7 or 8 months. The deeper answer to this is the implicit assumption when you ask how long it takes to build a new habit is, “How long does it take for me to get to the finish line?” That’s what you’re thinking.

I feel that that is the wrong angle to take if you’re trying to build better habits because the honest answer to, “How long does it take to build a habit,” is it takes forever because if you stop doing it, it’s no longer a habit. People need to start looking at habits as a lifestyle to live and not a finish line to be crossed. Once you adopt this mindset of this is a permanent lifestyle change, that’s another reason to pick small and sustainable 1% improvements that you can build into your life and stick with it over the long run. What you want is to become that type of person where that is the normal thing for you to do rather than, “I’ll push hard for three months and then this problem will be fixed.”

People need to start looking at habits as a lifestyle to live and not a finish line to be crossed. Share on XYou gave so many examples in the book of those baby steps. You didn’t change things overnight. You had to work on that one little behavior, and then that becomes how you think. It becomes part of you and then you add the next behavior. You’re right. We have to do it one baby step at a time. I know people who are tuning in are saying, “I’m overweight because of my family history or my gene pool of ancestry.” How does that play into the research that you’ve done?

Genes play an interesting role in habit formation. There are two ways to look at it. The first is that your genes present what I would call a matching problem for you and your habits. Let’s use an extreme example to make the point clear. If you’re 7 feet tall and you want to play basketball, then your genes are a great asset, but if you’re 7 feet tall and you want to be a gymnast, your genes are a great hindrance.

Some people often think, “I got this bad genetic hand.” It’s much more about matching your genes to the appropriate environment. Whether you’re 7 feet tall, that’s the great set of genes on the basketball court, but a terrible set of genes in the gymnasium. The thing to focus on is what is the right environment or context for your particular genetic makeup.

This brings me to my second point about genes. One way to think about this is through the lens of personality. The most rigorous personality test thus far is what’s called the Big Five or variance of the Big Five. It maps your personality on five different dimensions. The most common one that people are familiar with is introversion on one side and extroversion on the other, but there are other ones like agreeableness, openness to experience, and things like that.

There has been a variety of research too that shows some interesting things, specifically how your genes or genetic makeup is linked to this personality trait. For example, if you take a set of babies in the nursing ward, there was one study done where they would play a harsh noise on one side of the ward, some of the babies would turn toward the noise, and some of it would turn away from the noise.

What they found when they track these babies through their lives is the ones that turned toward the noise were more likely to be extroverts, and the ones that turned away from the noise were more likely to be introverts. There’s something going on there genetically where you’re hardwired from birth to have certain personality traits.

Another personality trait that is on the Big Five dimensions is conscientiousness, which essentially means if you’re high in conscientiousness, you’re pretty orderly and plan well. If you’re low in conscientiousness, then you’re maybe more free-flowing and not as much of a planner. You can imagine that for someone low in conscientiousness, this is how we’re going to tie it back to habits here, if this is your personality, you might have trouble remembering when to do the habit. If you leave it up to that, you’re not a planner. You don’t make lists and things like that.

For someone low in conscientiousness, having an environment that is designed to make habits easier for you might be a useful way to build better habits. I give more examples in the book. Essentially, if you get a handle on what your personality is, it might give you some insight into which levers to pull or areas to focus on that will be more fruitful for you when it comes to building better habits.

I like how you present that genes aren’t good or bad per se but how can we leverage them in our favor? If I’m not a planner, what do I need to do to put the cues in place to remind me to do what I need to do?

Genes are only useful within a particular context so it’s up to you to design the context that best fits your genetic package.

Here’s the reality. We’re in control. That’s why in my intro I said, sometimes we feel like that habit is out of control and that it’s happening because we’re not thinking about it. We have control. We just have to stop and think about it, and put those markers in place to help us be in control or feel like we’re in control.

At a high level, your habits are essentially a set of solutions that you come up with for the problems that you face over and over again in life. If you come home from work each day and you feel stressed and exhausted, then that’s a problem that your brain tries to figure out a solution for. Some people maybe play video games for an hour or watch TV. The second person maybe smokes a cigarette. The third person maybe goes for a run for twenty minutes. Any one of those solutions could become a habit that resolves the same recurring problem that you’re facing of feeling stressed and exhausted.

One of the core lessons and what you hinted at there is that the original habit that you build and the original solution you come up with is not necessarily the optimal solution, but we often don’t think about it. It’s non-conscious. We’re falling into that pattern over and over again because it resolves whatever this tension or problem that we’re facing over and over again. Once you realize that, then it becomes your responsibility to be more aware of what your habits are, and then to design more optimal habits rather than continuing to fall into that original path.

Downsides Of Building Better Habits

We like our story and our habits. We like to say, “I can’t because.” We love excuses as a society too. It’s unfortunate but that’s the reality. In the book, you also talk about some downsides of building better habits. Can you talk about that? It’s very interesting.

Essentially, habits are the prerequisites to mastery. What I mean by that is that high performance in pretty much any area requires you to master the fundamentals. If you want to play chess, for example, you need to be able to know where all the pieces move pretty much on autopilot before you start thinking, “This is the move I’m going to make and then my opponent will make this move because of it. I’ll then do that.” You need a clear space for your mind to think about the next level of performance.

It’s the same way in basketball. You need to be able to dribble with both hands without thinking about it before you can move on to like, “What offensive play should we run,” and things like that. In hockey, if we want to make that example, you need to be able to skate on autopilot. You need to be very fluent on skates before you can figure out what to do next or the more advanced levels of play.

This is true for pretty much any area. The more that you can automate something, the more you free up space to focus on the next level of improvement. There is a downside to building better habits, which is that in the beginning, you’re paying attention and practicing something but as you start to automate it, you stop paying attention to what’s going on because now you can do it good enough on autopilot.

There are a couple of research studies that show this. Your performance often has a slight dip after you build a habit. Now you can do it so well that you’re not paying attention to whether you make tiny errors. For example, surgeons. Early in their career, their skills are ramping up. They’re getting better and then they hit a little peak where they’re at their max a few years in. After they’ve been doing it for so many years, they stop paying attention a little bit and it declines a little bit from there.

The downside of building good habits is that you stop paying attention to those little mistakes. To overcome that, what we need is a process of reflection and review, a process of refinement so that we can stay aware of where we’re at and what we need to improve rather than letting ourselves coast and fall into this slight dip.

I do this personally with my habits in two ways. At the end of each year, I do an annual review where I ask myself three questions. The first is, “What went well this year?” The second is, “What didn’t go so well?” The third is, “What I’m working toward?” That’s a chance mostly for me to track my habits. I write down how many articles I wrote each year, how many new places I visited, and how many workouts I did. I then break that out by how many workouts per month and then what my average was per month and compare that to the previous year.

The whole purpose of the annual review is to reflect and give myself a baseline of what I did in that year rather than what I feel like I did. Six months later, I do the second part of this reflection review process where I conduct what I call an integrity report. The integrity report also has three questions. The first question is, “What are my core values?” The second question is, “How am I living by those this year?” It’s a chance to pat myself on my back. The third one is the most important question. That is, “Where did I fail to live by those values?”

Ultimately, what you’re looking for when you build habits is you want to become the type of person that you want to be. You want this desired identity to be reinforced. Integrity is living in alignment with your values. The interesting thing about integrity is you’re not going to find anybody who doesn’t think they have integrity. Everybody’s like, “Of course, I have integrity.”

Ultimately, what you're looking for when you build habits is you want to become the type of person that you want to be. Share on XUsually, the way that we get off track with that is not by making one grave mistake but by a bunch of just-these-once exceptions. You turn around 2, 3, or 5 later and you’re like, “My character is different than what I thought it was or what I feel like it was.” Those are the two processes. The annual review helps me track my habits, and the integrity report helps me make sure that my habits are in alignment with my values. Those are two ways that I use to try to avoid that little dip in performance and make sure that my habits are staying on the right track.

We have annual reviews at work. Why shouldn’t we do our annual review of ourselves and our personal lives? It makes sense. We should have a VA. Do you do anything with more frequency so that you’re measuring that you’re moving your needle to what you want to become?

Measurement

Measurement is an important question. I write about it in the book a fair amount, but there are two things to realize. Broadly speaking, I put habits into two different categories. The first category is things that you can automate. Once you build it, you don’t need to think about it again like flossing your teeth, tying your shoes, or unplugging the toaster each time you use it. There are a bunch of these little habits. If there’s a slight dip in performance for tying my shoes, I don’t need to worry about that. I don’t need to track it.

There’s the other category where there are a few things in your life and everybody’s got a couple that they do want to be good at. For me, it’s writing, photography, and weightlifting. Those are the three areas that I do want to improve. First of all, you don’t need to measure that whole first category. You can just measure the stuff that’s important. Secondly, whenever possible, I try to put measurements on autopilot.

My calendar automatically measures all the new places that I visit each year. I don’t have to worry about tracking that myself. For workouts though, I do track them manually and on a much tighter timeframe, which is what you’re asking. During each workout, I track every set and every rep. I then refer back to what I did the prior week to see what weight I should do this week. In that case, the feedback cycle is much tighter than once a year.

That’s going to depend on the actual habit. I do something similar for my business. It’s not every day but it’s weekly. Every Friday, I’ll review the stats and see where things are at. Each month, I review it as well. The time of the feedback cycle depends on the particular habit you’re talking about but sometimes it can be useful for it to be shorter.

I speak and teach at corporations with different skills like coaching, sales, service, and all those kinds of things. It’s so funny. For seventeen years, in every class I teach, the first thing I do when I get in the car is self-assess myself, “Why weren’t they engaged with that? What has changed? Was I off my game? How did I say that? Why did I say that?” I’m constantly self-assessing because I want to make sure the next time I teach that same class or speak in front of a group, that I do better and I push myself. I don’t ever want to start to do the downward spiral because that’s dangerous. You then become irrelevant and all those other things.

It’s a great habit because the only way to do that is for you to be on top of it and continually revisit it. If you don’t, then you’re going to have a natural decline.

Thank you for that explanation of short-term focus. I love that long-term. That annual review is important too. There’s another thing too, James, and I don’t know if you found this for yourself or with your clients, and after writing the book. It was cute how you said, “I do it so I can pat myself on the back,” when you do those annual cues. We don’t pat ourselves on the back enough. We’re always like, “I didn’t do that. I didn’t do this. I didn’t get there.” Instead of saying, “Look at all the things I did do though.”

The default mode of the brain is to identify problems. It has to be for you to survive because if you don’t realize, “I need to drink water and find food now,” or something like that, then you wouldn’t be able to survive. Your brain is always looking for whatever isn’t right as the default mode. We need these practices to make sure that we remind ourselves of what is right.

Your brain is always looking for whatever isn't right as the default mode. We need these practices to make sure that we remind ourselves of what is right. Share on XThere’s another effective measurement that can be very useful, which is that it reinforces your desired identity by turning the invisible into something visible. If you use a habit tracker and every time you make a sales call, you put an X on the calendar, or every time you go to the gym, you put an X on the calendar, if you’re trying to build that habit and you get to the end of the month, you see, “There’s fifteen X’s on the calendar.”

Maybe you’re having a bad day and you feel down. In that case, if you didn’t have the calendar, it’d be easy to think, “I’ve been working hard but nothing is happening. Nothing has changed.” If you see the calendar, then you can’t quite get as down on yourself because you have this visual evidence, “Fifteen times this month, I did go to the gym or make those sales calls.” It helps reinforce that you’re making progress even on the days when you don’t feel like it.

Especially with weightlifting or losing weight. You don’t lose weight immediately. All of a sudden, you’re not the Hulk because you’ve worked out for a month. We’re like, “My muscles aren’t big enough yet. What am I doing wrong?” Instead of waiting that extra week and then all of a sudden, you feel like you’re bulked up again.

Challenges Of Building Good Habits And Breaking Bad Ones

You can look at pretty much any behavior as producing multiple outcomes across time. Take a bad habit like eating a donut. The immediate outcome is favorable. It’s tasty and enjoyable. You like it right then. The ultimate outcome is unfavorable. You gain weight in a month or a week. Going to the gym or some good habit, the immediate outcome is often unfavorable. The reward for going to the gym for a week isn’t a whole lot. Your body doesn’t look different. The scale is the same. You are sweating and putting in an effort. The ultimate outcome doesn’t come until months later.

This is one of the challenges of building good habits and breaking bad ones. You need to find a way to take the long-term consequences of your bad habits and pull them into the present moment so you can feel them right then. Also, the long-term benefits of good habits and pull those in the present moment so that you have a reason to continue to show up while you’re waiting for those delayed rewards to arrive. People who are good at delaying gratification or appear to be that way from the outside are often good at finding alternative ways to be satisfied at the moment.

If you look at me from the outside, you might say, “He goes to the gym four days a week. He’s good at delaying gratification and waiting to get in shape and so on.” It doesn’t feel like that to me. What it feels like is, “I get to move and see some of my friends at the gym. I enjoy going because it reinforces the fact that I’m the type of person who doesn’t miss workouts.” All of those are immediate benefits. My focus is more on that rather than on waiting for the delayed reward or the scale to change. You can apply that to most areas. If you can find a way to be immediately satisfied, you have a good reason to show up again.

It’s another good habit to formulate though to be able to build those good long-term habits. That’s what you’re saying. Were you always very disciplined even as a kid? You’re very methodical in how you write. With us chatting, you’re very methodical in how you’re thinking. Were you always like that even as a kid?

I do think there are some aspects of my personality that are that way. Another big part of my disposition is being curious and being a learner. I’ve always been curious, questioning, wanting to learn new information, and trying to soak stuff up. I don’t know if I would describe it as methodical or as a desire for simplicity. I bring in all the information and then I want to simplify it so that it’s easier to understand. I’m constantly running that loop and going through that process.

It’s funny that you said that because in reading your book, I felt you were taking these very complex concepts. I’d be like, “That’s a good idea.” By the end of the chapter, you took that complexity and made it simple to say, “I can do that.” Throughout the book and the chapters that I read, I felt that you did a nice job of bringing the complex into simple. It’s important though because the average human thinks, “The more complex it is, the smarter I am.” Instead of, “The simpler it is, I’ll do that. I’ll get better at whatever that skill is for everybody that’s trying.” Simple works.

That’s a good way to summarize it, simple works. People sometimes like to hide behind complexity because it makes them sound smart but it’s more difficult to implement. I would rather use easy-to-understand language but have something that I can actionably use and apply in daily life. In a lot of ways, that’s my task. How can I find evidence-based scientifically backed strategies and make them very simple and easy to use?

People sometimes like to hide behind complexity because it makes them sound smart but it's more difficult to implement. Share on XFor everybody that’s tuning in, not only does James take the complex and make it simple but he used his personal stories and how he went from point A to point B to point C in very logical ways. There’s so much information about changing habits and how to get habits to stick. I’m older so as I’m reading your book, I’m thinking, “That will work. That’s another great idea.”

I’m telling you, it was hysterical thinking, “Why hasn’t this been thought of before?” That’s why I said to you early on that I feel like your book is revolutionary because it’s things we know but no one has ever simplified to the point of execution. Change happens when there are executable steps to create whatever it is that we’re looking to create. You simplified that. I have to say, I truly did enjoy the book and I hope people go buy it. Let’s tell them where to find you and how to find your book.

Thank you so much. I appreciate that. The book is called Atomic Habits and you can find it at AtomicHabits.com. If you go there, in addition to the book, there are also some additional bonuses. There’s a secret chapter that is not included in the book itself. There are some exercises and templates. Also, guides that help you put things together. There’s a five-step companion email guide that can walk you through the book and give you some additional resources and links to check out. You can find all of that at AtomicHabits.com.

The other thing too is you do take that scientific research and bring it into why it’s hard to create a habit. All of that stuff we talked about on the show was more of the scientific research on how psychology works and the brain works. You do a nice job of taking the scientific as well and showing us, “You’re not crazy that it’s hard for you to create a good habit.” You have all these natural things that work in us within our bodies and minds. It almost makes you feel like, “I’m not a crazy person when every time I try to create a new habit, I fail.” It’s because we have a lot of stuff on autopilot, unconscious beliefs, and all those things that affect it.

I say this in the book. If you’re having trouble changing your habits, the problem isn’t you. The problem is your system. Bad habits persist again and again because you have the wrong system for change. It’s not because you don’t want to change or you don’t know how to change. One of the purposes of writing Atomic Habits is to give people a step-by-step system they can follow for making good habits easier and bad habits harder.

Atomic Habits

You speak in the book about how you got the name Atomic Habits. It’s brilliant.

There are three meanings to the word atomic and all of them play into the book. The first meaning of the word atomic is that it’s tiny. That is a core part of my philosophy. Habits should be small and easy to do like an atom. There’s another meaning to the word atomic, which is that it’s the fundamental unit of a larger system. Atoms are built into molecules. Molecules are built into compounds and so on. In a sense, we could say that habits are the atoms of our lives. There are these fundamental units. These are behaviors and patterns that we repeat each day. When you start to put them all together, you end up with the system of your life and of behaviors that make up your day.

The third and final meaning of atomic is that it’s the source of incredible power or energy. That gives you the narrative arc of the book that if you can make small and easy changes, these little 1% improvements and little habits, and layer them on top of each other so that they’re the fundamental units in a larger system, eventually you’ll get this incredible outcome or this powerful result. The word atomic encapsulates all three of those phases.

I love the description of the book. Thank you for sharing that. I know we went a little over but it’s important because people are like, “Atomic habits. What does that mean?” There was a lot of thought that went into the title of the book so I thought it was important to share. Everybody, please go visit James’ website, JamesClear.com and check out the book at AtomicHabits.com.

He gives you a whole bunch of other insights, free information, and templates that will help you create the change that you’re looking for. James, thank you so much. Thank you for the book and for being on. Thank you for being a delight and being very articulate in sharing your vision but also sharing to help people become the better version of themselves. That’s awesome. Thank you for that.

Thank you so much. I appreciate it. It’s been wonderful chatting with you.

It’s a true pleasure. I hope you guys will all join me weekly as we question, build, and discover together how to grow and challenge ourselves so that we can embrace change. Use a book like Atomic Habits that James Clear has written to help us create that change that we’re looking for.

Important Links

- Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

- JamesClear.com

- https://LinkTr.ee/conniewhitman

- https://www.ChangingTheSalesGame.com/communication-style-assessment

- https://ChangingTheSalesGame.mykajabi.com/All-Star-Community

Stalk me online!

- Connie’s Website

- Connie’s LinkTr.ee

- Connie’s #1 International Bestseller Book – ESP (Easy Sales Process): 7-Step to Sales Success

- Download the FREE Communication Style Assessment

- Join our All-Star Community

Subscribe and listen to the Changing the Sales Game Podcast on your favorite podcast streaming service or YouTube. New episodes are posted every week on Web Talk Radio. Listen to Connie dive into new sales and business topics or problems you may have in your business.

James Clear is a writer and speaker focused on habits, decision-making, and continuous improvement. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Entrepreneur, Time, and on CBS This Morning. He is a regular speaker at Fortune 500 companies and his work is used by teams in the NFL, NBA, and MLB.

James Clear is a writer and speaker focused on habits, decision-making, and continuous improvement. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Entrepreneur, Time, and on CBS This Morning. He is a regular speaker at Fortune 500 companies and his work is used by teams in the NFL, NBA, and MLB.